The campus was beautiful and reminded me more of a college experience than a high school visit. I had designated Mwituha Secondary for my research work specifically because of the positive impression that the school left with me when I first visited. The children I met were friendly and eager to learn, the teachers seemed well-versed in their information, and the principal was clearly a leader and someone who cared deeply about academics. These qualities may seem like a given for every school, but as a former teacher I can attest that this combination is VERY difficult to find in the average school setting, whether it be Kenya, America, or anywhere else in the world. Even though this school is the farthest away from where I'm living in Kenya (a good 45 min. journey one way) I knew from the first moment that I saw it that it was an environment that I needed to learn more about. It's literally an educational gold mine.

One clear indication of this can be seen in all of the murals painted around the school. One day I had a conversation with the principal over lunch who informed me of his ideas about education. He believes that students should never be deprived of even the smallest opportunity to learn. This means that students should be immersed in education from the time they enter the campus until the time they go home. He called it a "bombardment technique," but I know it by another name used by one of my heroes, Geoffrey Canada. In the Harlem Children's Zone it's known as "contamination theory," and it encompasses surrounding children with protective factors so that they don't have the opportunity to succumb to all of the risks surrounding them. So, for example, when children walk into their school everyday, this mural of the school motto, mission, and vision is the first thing that they see. It is painted on a wall facing the main road outside of the school which makes it appear to be a sort of barrier to any who would choose to remain uneducated.

On the other side of the entrance children see paintings of young scientists doing work in Chemistry, Biology, and Physics. When I asked one of the school leaders if the school focused heavily on sciences the answer was, "No, but we want children to understand that even the most difficult and coveted jobs in Kenya ARE obtainable." I got chills down my spine! The entire school (teachers, administrators, etc.) seemed to be operating under a unified directive. It wasn't about establishing teacher's unions for higher pay or arguing over how to spend government dollars. This school simply wanted to produce students who could perform at high academic levels in order to achieve their dreams. What a simple, and yet beautiful, idea!

The leadership and influence of the principal could be seen everywhere around the campus.

This mural was located right next to the students' lunch area. When I asked the two guys in this picture if they would like to visit America someday, their reply was, "Yeah, but we've got to see the rest of Africa at some point too." Again, I got chills down my spine because these students, unlike many youth I've met here, didn't view America as their "savior." They understood the value of their own country and the rest of the continent of Africa and they viewed America as "just another country." That's powerful...and that's empowerment! I wish I had this aptitude when I was their age. It really is a rare gift.

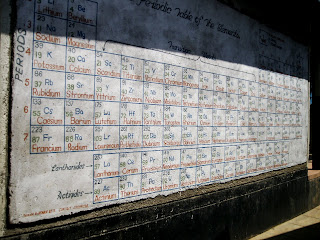

Outside of the science lab on the campus, students walked by this giant mural of the periodic table. Although I favored biology over chemistry I still admired this massive achievement. When I compared it to the periodic table on my phone (I used this when I taught science) it was just as accurate. The students here may not have massive textbooks complete with periodic tables in the back of them, but they do have this painting that they pass everyday. I can recall trying to get my students to memorize the first 20 elements on the table and saying to them, "If you just get these 20 down, all the rest will follow a pattern that is easy to understand." However, no matter how many times I emphasized this point, there would always be some students who never quite got it down. Now, I think to myself, "My students had access to things like a periodic table whenever they needed it. These students only get to see it when they come to school and pass it on a wall. So I wonder who values it more?"

Sitting in a classroom was also a very pleasurable experience. I've never seen students who are so eager to learn the information. I'm sure that part of this is due to the fact that the students here all pay for their education. In case you're wondering, NO, Mwituha isn't a private school! In Kenya the government only pays tuition fees for primary school (grades 1-8), so only children whose parents can afford to send them to secondary (high) school get a full education. In fact, many people in Kenya still don't complete, or don't go to, secondary school because their families simply can't afford it.

However, I've sat in numerous secondary school classes since I've been in Kenya, and for some reason this set of classes just felt...different. I don't know if it was the boy who asked the same question in 10 (not an exaggeration) different ways before he got the answer that he wanted, or the girl who held her hand up for 15 minutes as she patiently waited for her teacher to finish explaining a concept to another student. The students just possess this hunger to absorb the information that I've never seen . Earlier in the week I replied to an email from one of my best friends who wanted a quick comparison of the children in Kenya and America. I composed the following list:

1. The students here know more information than we did at this age.

2. The students are doing work that I didn't begin until I reached the university level.

3. They're simply smarter than we were at that age!

None of the items on this list are an exaggeration. (Although, #3 is relative and subjective) I ended my email to him by saying, "Man, if these kids just had computers and internet access, they could rule the world." I've never felt more excited AND frustrated at the same time. I kept thinking that with a few more resources at their disposal these children could perform at or beyond the levels of American children.

So you can imagine how surprised I was when a teacher asked me to teach one of his classes! "Why the shock" you ask? Here's a couple of things you need to know about this teacher.

1. He teaches EVERY chemistry course at the school.

2. His students produced incredibly high marks on the mock exams taken previously.

3. He had already covered THE ENTIRE SYLLABUS in the first 2 terms of the year.

I don't care how good of a teacher I considered myself to be in America, this dude was the real deal! But he insisted, stating that it would be good for the students to get an "American perspective," in their science educations. Now I've never been one to step down from a meaningful challenge, and to be honest the idea excited me quite a bit, but to say that I was intimidated was an understatement. So I said, "Sure, what do you want me to teach?" And without missing a beat he said, "The students need to review their Organic Chemistry molecules. How about a review of Alkanoic Acids, including their nomenclature, structure, and lab preparation?"

(If you're reading over that last sentence and saying 'huh?' to yourself, don't worry I was thinking the same thing at the time. I hadn't learned, let alone discussed, that material since my sophomore year of college!)

Again, my name is Patrick Banks, and I refuse to step down from meaningful challenges, so I said, "Sure, just give me a day to prepare." With that I smiled, grabbed a copy of the science syllabus, and headed home to start re-teaching myself this material.

The next morning (D-day as I called it) I was ready to show these advanced students what I had. When I met the Chemistry teacher at the school he had no idea that I had stayed up the previous night for about 7 hours learning and condensing the information down into a lesson plan for high school students. He didn't know about the two cups of coffee I drank to be more alert for the lesson, and he couldn't see the excitement and anticipation in my eyes to do a review with these students. The next thing I knew, I was standing in front of the class in full swing, and surprised at how quickly the "teacher mode" was coming back to me. I had my summarized notes down, I had accurately anticipated the questions that the students would ask, and I gave them plenty of practice opportunities so that they could demonstrate their mastery of the material. The entire time the teacher sat in the back of the room, never saying a word, showing ZERO non-verbal body language cues, and keeping a stern look on his face. But after the lesson he grabbed my hand with the biggest smile on his face and simply said, "Good job."

After I left the class the principal stepped in and surveyed the students on my performance. While this seemed very intense to me, it echoed his desire to ensure that his students were getting a meaningful education. To my surprise he walked into the staff room where I was waiting and congratulated me on a job well done. He said that the students approved of my teaching, with my only advice being that I needed to slow down my speaking because English was, after all, their second language. It felt good to know that I hadn't hindered the education of these amazing students.

Now a new struggle begins. How can I take this awesome Kenyan school model and apply it to the American educational system? As we all know it's difficult to point a finger at our failing school system and say, "You should do this...blah blah blah." But the information I'm learning through my journeys here is invaluable. I guess I'll be using the rest of my time here to think about that...

2 comments:

Yep. I'm jealous! :-)

AWESOME!!! You are so on point with your observation on the education (British?) system in Kenya and how the students value it more because their parents sacrifice a lot to keep them in school.

I look forward to talks with you!

PS: My Chemistry High School teacher in Western Kenya beat us up if we weren't able to i.d the first 20 elements on the periodic table...Bless his heart, I have never forgotten it, or the cains.

Post a Comment